A former judge accuses retiring Supreme Court Chief Justice Russell Anderson of playing politics

Judgment Call

When Russell Anderson announced last month that he'd be stepping down in June as chief justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court, the reviews of his two-year tenure were glowing.

"We have appreciated his wise leadership of the court and his insistence on the impartiality of the judiciary," editorialized the Pioneer Press.

The Star Tribune was no less effusive. "Russell Anderson's relatively brief tenure as Minnesota's chief justice belies the lasting impact he'll have on Minnesota courts and those who seek justice in them," the newspaper's editorial board cheered.

Gov. Tim Pawlenty hailed Anderson as an "extraordinary leader and public servant."

In particular, the 65-year-old chief justice was applauded for his efforts to keep partisan politics and special interest money out of judicial races. "Nobody wants somebody calling balls and strikes before the pitch is thrown," Anderson has been quoted more than once as saying.

But up in Anderson's hometown of Bemidji, Terrance Holter experienced a very different reaction to the news. He wondered if his strange, two-year odyssey through judicial politics might have something do with Anderson's retirement plans.

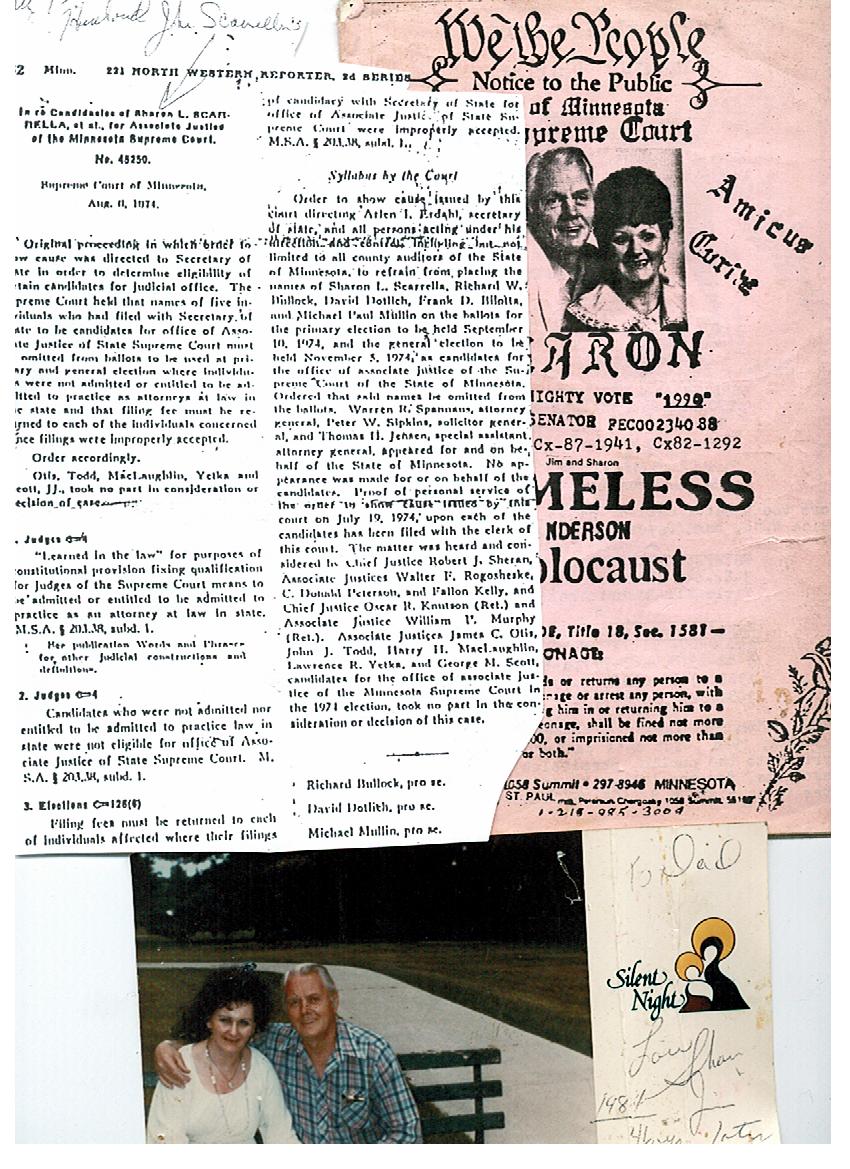

Holter and Anderson have known each other for most of their lives. They both grew up around Bemidji, the northern Minnesota town of 12,000 that's best known for its statues of Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox. Holter was two years behind Anderson at Bemidji High School.

After graduation, their lives continued to converge. Both eventually established law practices in the Bemidji area, with Anderson advancing to become the county attorney. Each was tapped in the early 1980s by Gov. Al Quie to serve as a judge in the Ninth Judicial District.

But Holter's tenure as a judge came to an abrupt end two years ago when he was defeated at the polls, and he blames his judicial exile in large part on meddling by the chief justice.

"This has been such a kick in the teeth all the way around," says Holter. "I wouldn't try to pretend I'm not angry about the whole thing."

ON THE LAST DAY of candidate filing in July 2006, Judge Terrance Holter was on vacation. The 26-year veteran of the bench spent the afternoon visiting relatives. He figured he had little to worry about. After all, he hadn't faced electoral opposition since the end of his first term on the bench more than two decades earlier. Even then, Holter's opponent was a perennial gadfly who posed little threat at the polls.

But that July evening, the veteran jurist received some surprising news via a phone call from a fellow Ninth Judicial District judge. Not only would Holter face opposition in the fall elections, but two different candidates had filed to run against him.

One was Tim Tingelstad, a conservative Christian who wanted to bring religion into the courtroom.

But the real shocker was Holter's other opponent: John Melbye. For the previous four years, Melbye had served as Holter's law clerk. They'd had an amicable relationship, partnering up on the golf course and exchanging presents at Christmas.

Unbeknownst to Holter, Melbye had resigned via letter and cleaned out his office over the weekend.

"I couldn't believe it," Holter says. "I thought, What a snake." (Melbye declined to comment.)

Holter quickly realized that he had no clue how to run a political campaign. And the Ninth Judicial District presents a particularly bewildering electoral landscape, stretching over 17 counties from International Falls on the Canadian border to Brainerd in the center of the state. Although Holter could preside over cases in any of the 17 counties, more than 90 percent of his work was in the Beltrami County Courthouse in Bemidji. "There are many counties in the district that I've never set foot in as a judge," he says.

When Holter returned to his office a couple of days later, he found a phone message from local attorney Rebecca Anderson. She wanted to help with his campaign. At the time, this seemed like a fortuitous development. Not only did Anderson have strong ties in the legal community throughout much of the Ninth Judicial District, she also happened to be the daughter of the chief justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court, Russell Anderson. In fact, Holter says, Rebecca Anderson told him that she was calling at her father's behest.

"She said, 'My dad called me last night and said you've got to help Terry,'" Holter recalls. "I thought that's great. You've got the Supreme Court chief's daughter. She says she knows how to run a campaign."

Rebecca Anderson immediately signed on to be the co-chair of Holter's campaign. But as Holter describes it, her stewardship of the re-election effort was a disaster from the outset. She never made good on promises to deliver endorsement letters from prominent local citizens. She also failed to set up appearances at church suppers and county fairs where Holter could hobnob with constituents.

Meanwhile Melbye was running an extremely vigorous campaign. The son-in-law of cable magnates, Melbye spent roughly $25,000 of his own money, ensuring that this would be among the most heavily funded campaign in the history of the Ninth Judicial District.

"I had never seen a judicial campaign like this before," says Carl Drahos, a veteran Bemidji attorney. "I just hadn't seen that kind of campaign money flowing in my life."

Owing to the size of the district, and the low level of interest in judicial races, money has the potential to play an outsized role in election outcomes. "I don't want to say it's unfair, but I think it's a risk of the result being more a fact of exposure and spending money to campaign as opposed to strictly the qualifications," says Jon Maturi, chief judge of the Ninth Judicial District.

At the time of the 2006 race, most of the media's attention was focused on Tingelstad's candidacy. In the wake of an appeals court ruling striking down restrictions on partisanship in judicial campaigns, Tingelstad received the endorsement of the GOP, making him the state's first judicial candidate to have party backing. He also ran a campaign that promised to bring religion into the courtroom. His electoral slogan: "Justice is served when judges fear God and love the people."

But voters in northwest Minnesota showed considerably less interest in Tingelstad. Holter and Melbye each garnered 39 percent of the vote in the primary election, with Tingelstad a distant third.

The results didn't exactly bode well for the incumbent judge. Despite more than two decades on the bench and an opponent who had never tried a case in a courtroom, the race was a dead heat.

The Holter campaign redoubled its efforts, enlisting prominent attorneys to write letters to the editor making the case for his re-election. "You can learn a lot during a clerkship, but not enough to take the seat you've served," wrote local lawyer Eric Shieferdecker. "Judges should be cut from stronger, more mature timber."

But Rebecca Anderson failed to deliver the letter to the newspaper as promised, Holter claims. She also assured him that Polk County would be friendly territory, given that she'd attended high school in the area while her dad served as a district court judge. But Holter says she failed to set up a single campaign event in the area.

Although Holter feared that her failure to follow through on such promises might cost him the campaign, he hesitated to confront her about the problems. After all, he didn't want to offend the daughter of the chief justice of the state Supreme Court.

On election night Holter went to the movies to distract himself from the pending results. Around 10 p.m., he and his wife began tracking the tabulation online. From the outset, Melbye maintained a small lead. By about 1 a.m., it was clear Melbye would narrowly win the bench. He ultimately garnered 51 percent of the ballots, besting the incumbent by roughly 1,500 votes.

Holter lost the election despite the fact that he carried his home turf—Beltrami County, where he'd tried the overwhelming majority of his cases over the prior 26 years—by a robust 62-38 margin. He also won neighboring Hubbard and Clearwater counties, where he'd occasionally worked over the years.

Holter blames the loss in part on Rebecca Anderson's failures as a campaign co-chair. "She didn't do anything," the judge says.

But Rebecca Anderson, who has since relocated to the Twin Cities, disputes Holter's characterization of her efforts. She points out that she was merely a volunteer trying to assist the campaign. "I felt horrible," she says of the election defeat. "My whole intent behind it was just to help Judge Holter."

She also denies that her father asked her to get involved with the campaign. "I had told my dad that I was going to offer to help," she says. "I heard rumors about this, but no, my dad wasn't behind it. It was my decision."

Russell Anderson declined to be interviewed for this article. But in a statement released to City Pages, a Supreme Court spokesman denied that Anderson asked his daughter to help Holter's campaign. "She was a lawyer practicing in the same town as the judge and offered without any prompting by the chief justice to help the judge gain reelection."

SEVERAL WEEKS AFTER the disappointing election loss, Holter received a phone call from John Smith, then chief judge of the Ninth Judicial District. Smith suggested that Holter retire before his term expired at the end of the year—that way Holter could sign up to serve as a retired judge and fill in for jurists who were on vacation or medical leave.

So just before Christmas, Holter turned in his resignation and filled out an application to serve as a retired judge. Because he'd lost the election, Holter would need special approval from the Minnesota Supreme Court, specifically Chief Justice Russell Anderson. No problem, Holter thought.

But a couple of weeks later, Holter got word that Anderson wanted to sit on the application for six months while things "cool down."

"It baffled me," Holter recalls. "There wasn't anything to cool down."

In March, Holter got another call from Smith, who was hoping Holter would be able to fill in for him during an upcoming absence. Smith called Anderson to press him on Holter's pending application, but the chief justice didn't budge.

In April, the judges of the Ninth Judicial District held their quarterly meeting. During the gathering, they passed a unanimous resolution supporting Holter's application to serve as a retired judge.

Despite this show of support, Holter got word in June that Anderson wasn't going to accept his application.

Bewildered by the decision, Holter lobbied various local officials to write to Anderson on his behalf. Among those who offered support: the Beltrami County attorney, the chief public defender for the Ninth Judicial District, a local representative of the American Civil Liberties Union, a Beltrami county commissioner, and several prominent local attorneys.

"Judge Holter is a highly respected Judge in the Beltrami County area," wrote Sheriff Phil Hodapp. "Judge Holter is highly thought of by the law enforcement professionals who have worked with him over the past couple of decades."

Anderson's response to each supporter was brief and free of sentiment. "It has been the policy of former Chief Justices to not appoint district court judges, defeated for re-election, to serve as retired judges," he wrote. "It is a policy I will continue."

Finally, in September, Holter received a phone call from the chief justice. During the five-minute discussion, Anderson acknowledged that Holter had considerable support, but refused to back down from the decision, citing the potential for a public backlash if Holter was permitted to serve on the bench after being rejected at the polls.

The phone conversation was civil, but the way events played out continued to gnaw at Holter. Unable to put the matter out of his mind, Holter wrote to Anderson directly. He laid out their numerous personal connections, from time spent as judicial colleagues to the intimate role Anderson's daughter played in Holter's campaign. Holter's main point was that the chief justice should recuse himself from the decision.

"I have reason to believe that your decision was based, at least in part, on a personal animus toward me," Holter wrote. "However, even if that was not the case, you couldn't possibly have been neutral to me."

The response from Anderson was silence. To this day, he refuses to sign off on Holter. In a statement to City Pages, Anderson reaffirmed his stance that judges who lose elections should not be allowed to serve as retired jurists. Holter is uncertain whether the decision will be open to reconsideration after Anderson steps down in June.

In the meantime, Holter is trying to enjoy retirement. He spends his days reading, meeting friends for coffee, golfing, and supporting Bemidji State University sports teams. But the whole strange series of events continues to eat at him.

"It just angers me the way the whole thing played out," he says. "I just can't rest easy."